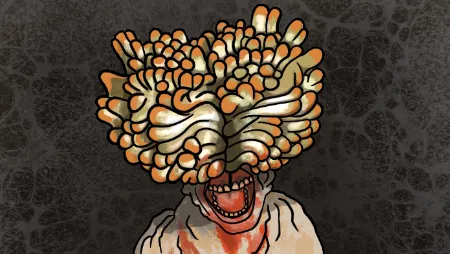

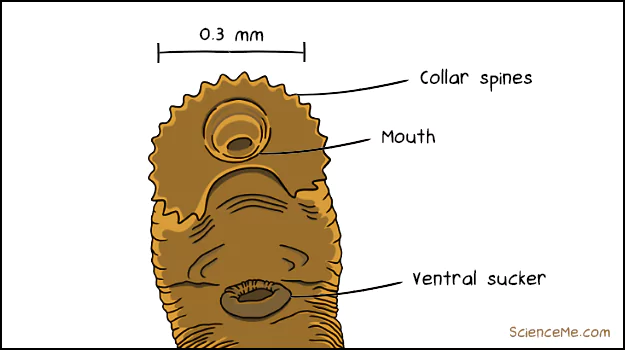

This is the parasitic flatworm, Curtuteria australis. He lives in three hosts during his convoluted lifecycle. Best of all, he's a card-carrying body-snatcher who drives his host to suicide like some terrifying mashup of The Happening and The Last of Us.

Like most worm species, Curtuteria is a hermaphrodite with both male and female sex organs. This suits it rather well when there are limited mating opportunities (which is quite often when you're an internal parasite). In a lifecycle that lasts just a few weeks, this particular species of flatworm must sequentially infiltrate the bodies of two molluscs and one bird out on the mudflats of New Zealand. If he fails, he'll die. If he succeeds, he'll also die. But he'll die a smidge happier.

Curtuteria australis is one of more than 20,000 flatworm species.

Part I: Hatching and Cloning

Curtuteria australis, or Curt if you will, starts life as a fluke egg in the gut of an oystercatcher bird. When the bird defecates, Curt and his fellow eggs make a gentle landing on the coastal mudflats.

This is where the easy ride ends. Having been shat out by a bird, Curtuteria australis and his friends are about to be consumed by whelks; predatory marine snails with pointed spiral shells. To some humans, whelks are delicious. Even when they know that whelks are riddled with parasites. Similarly for Curt, whelks are at once terrifying and appealing hosts.

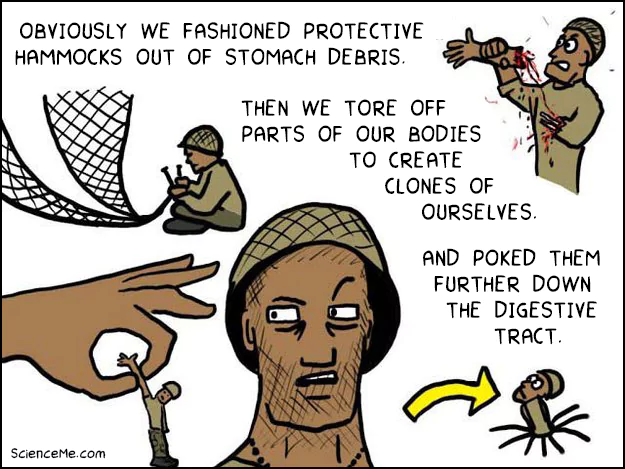

Deep inside the digestive gland of the whelk, Curtuteria hatches into a larval worm. Without a moment to lose, he goes through a type of asexual reproduction called budding. Budding is more than a bit weird. It involves growing new body parts which then fall off so they can develop into entire clones. Corals, flatworms, jellyfish and sea anemones are very good at this.

When you and your clones find yourselves in the intestinal cavity of a whelk, there's really only one exit strategy. For the second time in his miserable life, Curt is expelled from an anus. This time he ends up in the ocean.

This mass die-off is typical for young Curtuteria. Survival is a numbers game when you reproduce on mass and don't bother taking care of your babies. Curt, now a juvenile flatworm, is lucky to survive. He can now look forward to being eaten alive by his next host.

Part II: Body-Snatching

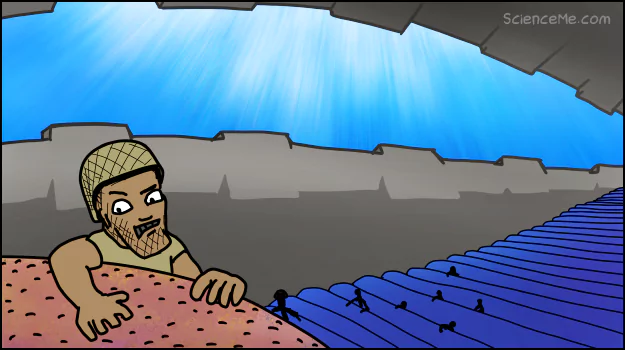

Next, Curtuteria australis is siphoned up by a cockle; a bi-valve shellfish that's closely related the clam. These marine molluscs eat and breathe by siphoning water over their gills, and filtering out the phytoplankton and oxygen. When an unsuspecting cockle filters our body-snatching parasite, it effectively sentences him to death.

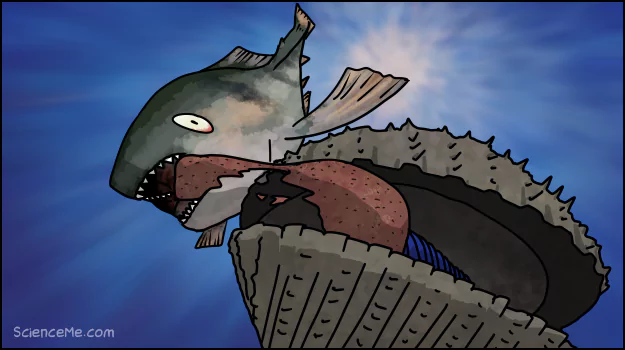

Curtuteria instinctively makes his way deep into the cockle's muscular tissue. We'll see why in a moment. But this is more risky business for Curt: cockle flesh tastes delicious according to the Spotty fish, who's always on the lookout for a tasty bit of protruding meat. Curt must hide deep within the cockle's tissues or die a virgin and fail to pass on his ridiculous genes.

Once the Spotty fish moves on, Curt can convince the cockle to die in a more appropriate manner. How? Cockles move in two ways. Underwater, they're carried by tides and ocean currents. And on land, they extend their muscular body out of their shell to burrow into the sand.

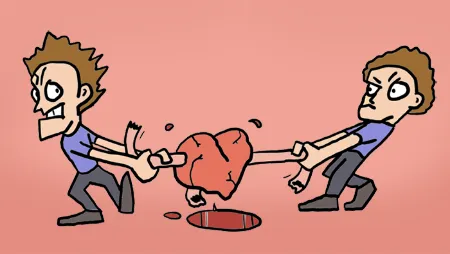

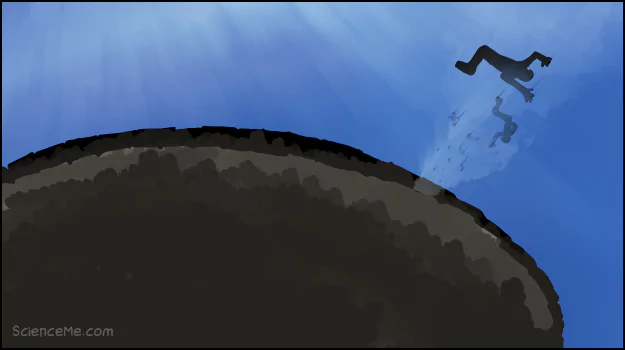

But Curtuteria is about to ruin it all. He and his flatworm buddies form hard cysts inside the cockle's muscular foot, causing it to atrophy and shrivel. Soon, the muscle becomes useless for digging into the sand.

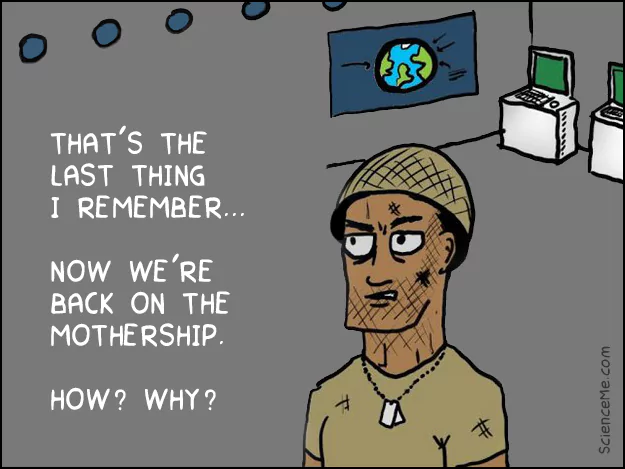

At low tide, the cockle is beached. It can no longer dig itself underground to evade predation, and just lies there pitifully on the mudflats. What's Curt thinking? Rule number one in Parasitism for Dummies is don't kill your host—isn't it? Actually, if you're done with your present host, killing it is a very convenient way of finding your next host. The best way to do this is to drive it into the chops of a predator.

Part III: Cross-Fertilisation and Egg Laying

The dragon is in fact Curt's primary host—an oystercatcher bird. It finds the stranded cockle lying on the mudflats and feasts on the infected flesh.

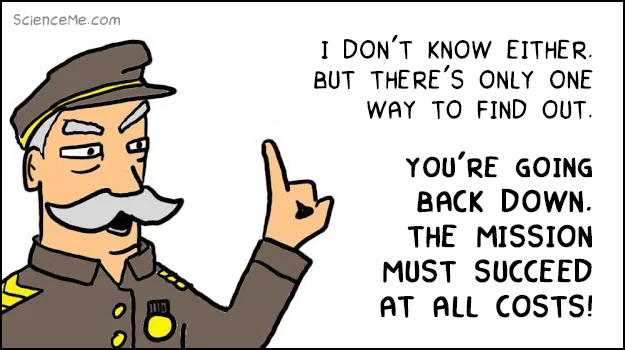

Inside in the bird's gut, Curtuteria matures and reproduces sexually. Ideally, he achieves cross-fertilisation by teaming up with another hermaphrodite flatworm. This sees them both exchange sperm and fertilise each others' eggs. Soon Curt lays a fresh batch of eggs inside the bird, and the whole horrible cycle begins afresh.

This is how the lifecycle of Curtuteria australis exists today. It's just one of countless parasitic species that do disgusting things to other animals in the name of survival.