Gene therapy is a cutting-edge technology that delivers healthy DNA into malfunctioning cells to restore lost biological function.

Treating disease at the level of genes is elegant in principle but messy in practice. This is the story of how researchers have overcome incredible barriers to:

- safely transfer and integrate genes into cells

- conserve the new genes when cells divide

- troubleshoot rapidly when gene therapy goes wrong

Before we look at the mechanics of gene therapy, it's helpful if you know the basics of how DNA works.

What is Gene Therapy?

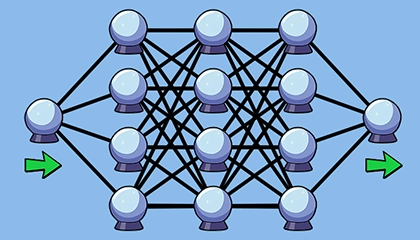

Your entire genome resides in almost every cell in your body. However, to enact targeted cures, gene therapies are only applied the specific cell types causing disease. But how do you get new genes into cells? Researchers leverage what already exists in nature: viruses.

For billions of years, viruses have evolved to target specific cell types and inject their own genes. Infected cells automatically convert the viral genes into proteins, which assemble into new viral particles.

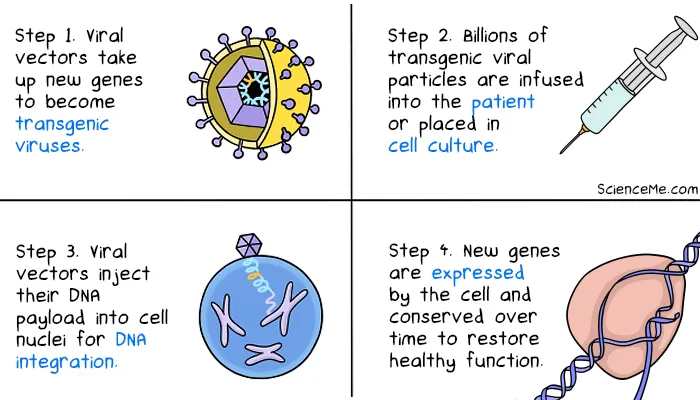

Exploiting viruses in nature effectively hacks the hacker, altering viral genomes and allowing them to carry therapeutic DNA payloads direct to target cells. Here's how that looks in practice:

While clinical trials began in the 1980s, the first gene therapy was approved by the FDA for general use in 2017. Brand-named Luxturna, it uses an AAV2 (adeno-associated virus 2) vector to deliver the human RPE65 gene into retinal pigment epithelial cells to produce the functional RPE65 enzyme essential to healthy vision.

The field has grown fast since then. As of 2025, nearly 40 therapies have been approved worldwide across rare diseases and cancers. Most use viral vectors, although a growing number use synthetic vectors like lipid nanoparticles (LNPs). They generally fall into two categories:

- Gene replacement therapy introduces new protein-coding genes to treat loss-of-function diseases like spinal muscular atrophy, or suicide genes to program cell death in cancerous tumours.

- Gene silencing therapy turns-off disease genes by marking faulty messenger RNA for destruction before it can be translated into harmful proteins, such as the amyloid-forming protein.

Current gene therapy trials target rare single-gene disorders and otherwise incurable cancers, with each disease demanding its own custom therapeutical protocol. Eventually, it's hoped that gene therapies will offer cures for multifactorial conditions like heart disease and neurodegenerative disorders, rather than just managing symptoms with chronic medication.

How Does Gene Therapy Work?

Let's get down into the details. Consider the process of gene replacement therapy to treat a loss-of-function disease:

Step 1. Vector Creation

First we need to select and engineer the ideal vector to deliver the therapeutic gene into the cells. Standard genetic engineering techniques are used to physically remove the replication genes from the viral genome. This prevents the virus from replicating uncontrollably in the patient's body.

The therapeutic gene, or transgene, is inserted in the space created in the viral genome, along with regulatory sequences like promoters to aid expression. The only viral sequences left behind are non-coding regions needed to pack the DNA up in the viral shell and target the desired human cells.

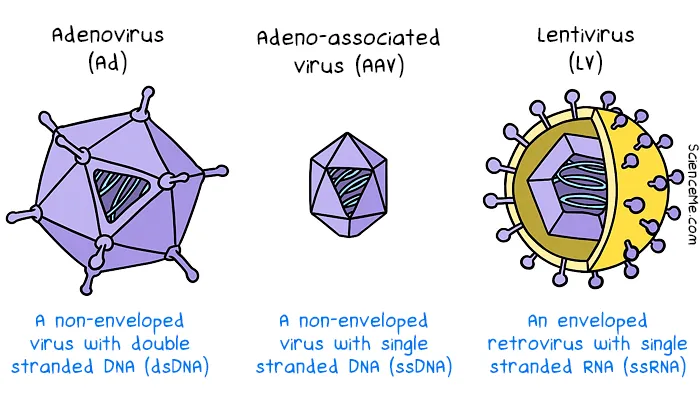

In gene therapy, the most suitable vectors tend to be adenoviruses, the tiny adeno-associated viruses, or lentiviruses. Selecting the best viral vector and dosage is a balancing act to maximise DNA delivery while minimising immune response and integration errors.

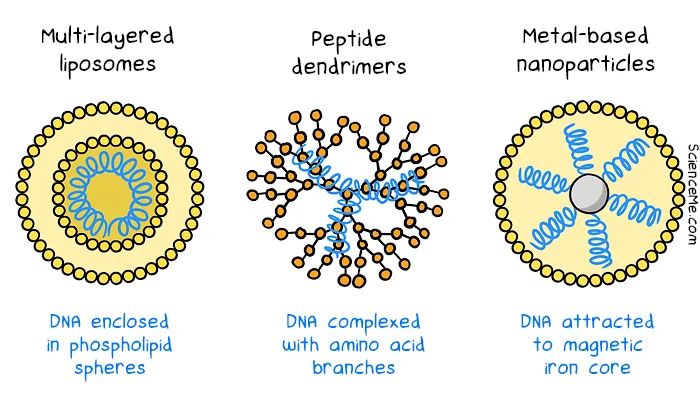

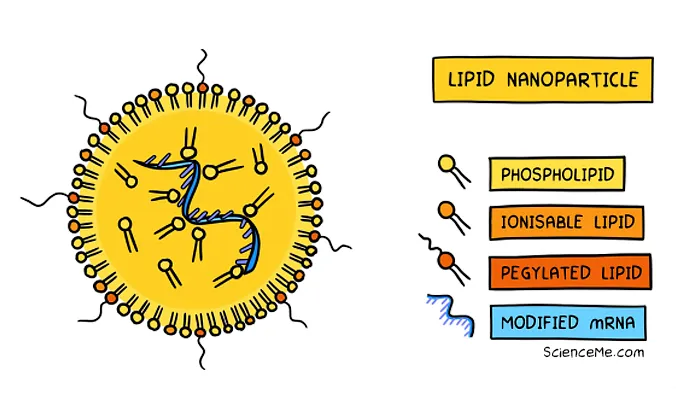

Synthetic vectors trialled in gene therapies laid the groundwork for using lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) in mRNA vaccines. Since the rollout of COVID mRNA vaccines, there has been more interest in developing more efficient non-viral vectors in gene therapy. Multilayered liposomes, peptide dendrimers, and metal-based nanoparticles are designed from scratch to deliver DNA to cells. While they tend to evoke a smaller immune response, they also have lower rates of gene delivery.

Step 2. Gene Delivery

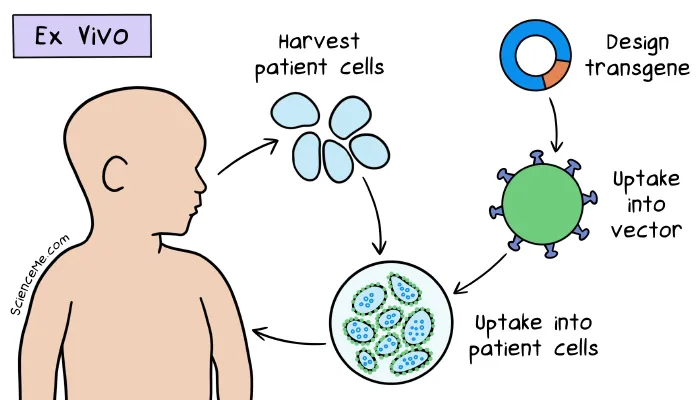

The vector can now be introduced to target cells at scale, either in the bloodstream (in vivo), the target organ (in situ), or in cell culture (ex vivo) for later infusion into the patient.

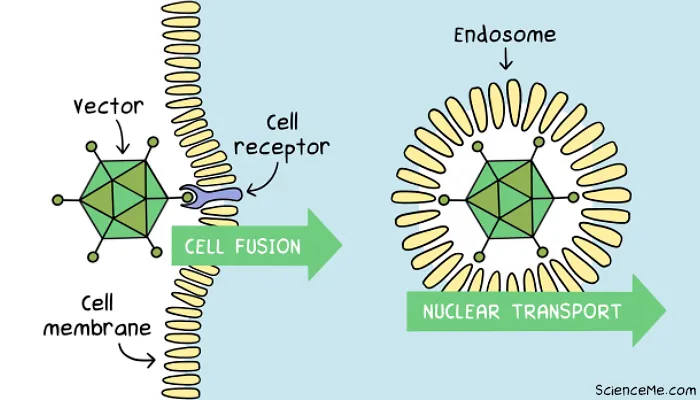

When a vector meets a cell, it must successfully gain entry at the cell membrane and deposit the DNA payload, without triggering a major intracellular immune response that destroys the cell.

Transduction sees the engineered virus fuse with with a cell membrane receptor for absorption into the cell via lipid bubble called an endosome. In synthetic vectors, transfection occurs when the carrier is absorbed by the cell via endocytosis.

Step 3. DNA Integration

Once inside the cell, both viral and synthetic vectors must achieve endosomal escape to free themselves of the lipid transport bubble and target the nucleus.

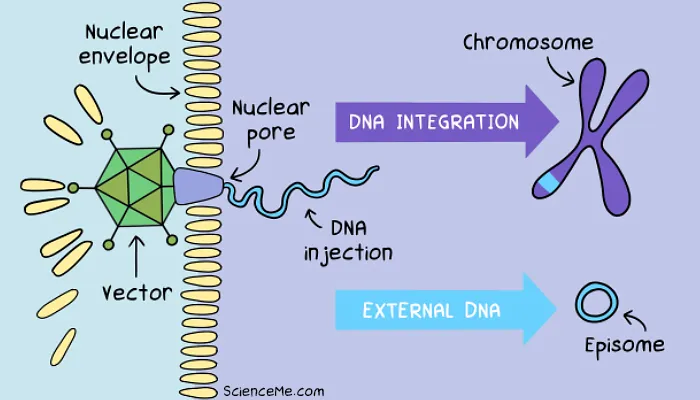

Viruses like AAVs and lentiviruses are recognised by the cell's nuclear transport machinery. Thanks to our co-evolution with viruses, they're chaperoned to nuclear pore complexes where they inject their DNA payload.

Synthetic vectors use a simpler workaround. They enter the nucleus via passive diffusion when the nuclear envelope breaks down during cell division. When the daughter cell forms, the therapeutic DNA is trapped inside the new nucleus.

Once secured in the nucleus, there are two ways the new gene can stick around for permanent expression alongside the host DNA:

Chromosomal Integration. Lentiviruses use an enzyme called integrase to physically cut a break in the chromosomal DNA and paste the viral genes randomly into the genome. While this carries a risk of interrupting existing genes (as we'll see later when gene therapy goes wrong), it's a reliable way to create permanent gene expression.

Episomal Permanence. Episomes are circular DNA molecules that never fully integrate with chromosomes. AAV vectors are a prime example, dropping episomal DNA alongside chromosomes for transcription, and remaining stable in non-dividing cells like neurons, muscle cells, liver cells, and retinal cells. In dividing cell types, engineered elements like scaffold/matrix attachment regions anchor the episome to the nuclear matrix, allowing it to be replicated alongside chromosomes without the integration risk.

Step 4. Gene Expression

Finally, the cell has the correct protein-coding gene it always wanted. General transcription factors bind to the promoter region and kick-off the process of unwinding and replicating the DNA as messenger RNA before sending it outside the nucleus to be expressed as a new protein. Here's a more detailed breakdown of DNA transcription and translation if you're into it.

Gene Therapy vs Genetic Vaccines

This may all be starting to sound like the same technology used in genetic vaccines. And you'd be right. So what's the difference between DNA and mRNA vaccines, like those developed for the SARS-CoV-2 virus, and your typical gene therapy?

DNA Vaccines

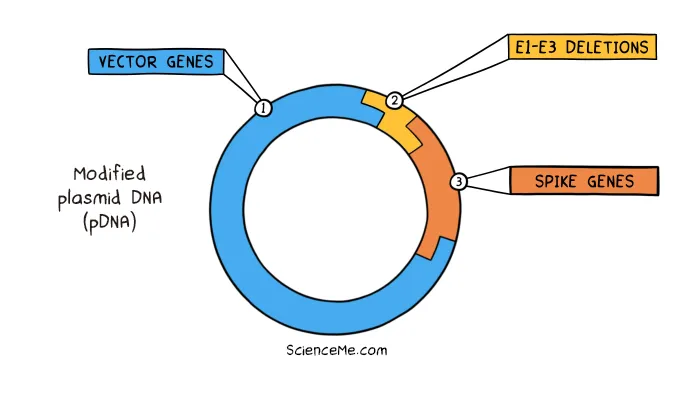

The DNA vaccines made by AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson are based on the plasmid DNA of an adenovirus. As with gene therapy, the viral pDNA is modified to remove its replication genes and make space—in this case to add the spike genes of SARS-CoV-2.

On injection into your body, the modified adenovirus enters muscle cells and injects its pDNA into the nucleus. Transcription and translation of the engineered plasmid sees the cell produce the viral antigen that trains up the immune system on SARS-CoV-2.

You'll be pleased to know that while pDNA is similar to episomal DNA, it lacks the machinery to integrate itself into chromosomes or attach itself to the nuclear matrix. When the cell dies or divides, the pDNA is lost. This is why the genetic effect of DNA vaccines is short-lived; the antigen is produced over several days or weeks before the DNA breaks down.

Messenger RNA Vaccines

The mRNA vaccines by Pfizer-BioNtech and Moderna use synthetic lipid nanoparticles to deliver the spike genes to the cell cytoplasm. This has the same effect of producing spike proteins without any access to the cell nucleus. It's also worth noting that mRNA degrades quickly and is shorter-lived than pDNA.

While genetic vaccines are based on the same principles and technology as gene therapy, they don't produce permanent gene expression.

Genetic vaccines have a short-term action by design. The same result would be a disaster in gene therapy, which must achieve permanent gene expression to be effective. Indeed, such long-term effects are incredibly difficult to achieve and the conservation of DNA remains one of the biggest challenges in gene therapy.

| Gene Therapy | Genetic Vaccines | |

| Genes | Human | Viral |

| Vector | Viral/Synthetic | Viral/Synthetic |

| Dosage | High (e.g. 3x1014 AAV) | Low (e.g. 5x1010 Ad) |

| Delivery | Intravenous | Intramuscular |

| Integration | Yes | No |

| Expression | Permanent | Temporary |

The Challenges of Gene Therapy

The hard part of gene therapy is ensuring the new DNA is delivered to the cell nucleus intact, and then conserved through many cycles of cell replication. It's essential that the healthy genes are copied in dividing cells to produce the lasting therapeutic effects.

But we can't go in guns blazing. Scaling the delivery of gene therapy can induce a deadly immune response, while boosting gene expression can activate dormant cancer-causing DNA.

This is why most gene therapies are at the pre-clinical stage (ie, animal studies) or the clinical stage (ie, human trials), where they're examined for efficacy, side effects, adverse events, and long term outcomes.

There are many complex variables surrounding the technology itself. Depending on the disease, faulty genes may be swapped out entirely, repaired using selective reverse mutation, or deactivated through gene regulation. This necessitates different forms of genetic material, including DNA, mRNA, siRNA, miRNA, and others.

There's no one-size-fits-all solution to curing disease at the genetic level. This is why it will be many years before we have a full suite of gene therapy treatments.

The principles of gene therapy are elegant. Yet in practice, some elements of the execution have been described as crude—and as we'll see in a moment, vulnerable to catastrophic failure. Nonetheless, experts believe gene therapy will eventually become a staple of 21st century medicine.

The First Gene Therapy Trials

In 1986, Ashanti DeSilva was born without the ability to make a protein called ADA, which plays a crucial role in white blood cells.

At birth, Ashanti seemed like a healthy baby. But as she became exposed to bacteria and viruses in the environment, her ADA deficiency became manifest.

"Ashi had her first infection at just two days old. By the time she was walking, she was constantly hacking and dripping with coughs and colds." - Ricki Lewis, The Forever Fix: Gene Therapy and The Boy Who Saved It

Most infants with ADA deficiency don't survive past their second birthday. Ashanti was lucky. After being diagnosed with Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID), she was put on protein replacement therapy using ADA sourced from cows.

Although the treatment was only partially effective, it kept Ashanti alive until she was four years old and recruited for one of the first gene therapy trials.

A sample of Ashanti's white blood cells was cultured in the lab and transfected with modified retroviruses carrying healthy ADA-coding genes. The sample was then infused into her bloodstream over the course of 20 minutes.

In Ashanti's ex vivo gene therapy, a retrovirus vector was modified with the deletion of viral replication genes and the addition of healthy ADA genes.

The gene therapy trial was a success. Millions of modified white blood cells began to produce ADA immediately, enabling Ashanti to make functional antibodies. The edited cells also went on to replicate with the new genes intact, providing long-term effects.

Although she needed 10 more infusions, Ashanti suffered no side effects from the ex vivo therapy, and was cured of SCID over the next two years. Today she's alive and well, married and with a Masters in Public Policy.

Ashanti's treatment prompted researchers to treat newborn babies with ADA deficiency in the same way. They even took white blood cells straight from the umbilical cord, enabling the infants to produce healthy immune cells from the start of their lives.

When Gene Therapy Goes Wrong

The first spectacular failure of gene therapy came nine years later, in 1999. It involved 18-year-old Jesse Gelsinger, who had a partial OTC deficiency which meant he couldn't effectively break down ammonia, a waste product of protein.

Without treatment, babies born with severe OTC deficiency die in the first few weeks of life. Jesse signed up to a gene therapy trial to help such infants, knowing he wouldn't be cured himself as the gene therapy effects would be transient.

The trial used the adenovirus 5 (Ad5) vector for delivery in situ, sending the virus directly to the liver for transfection. It had never been tested in humans before.

As the eighteenth and final patient in the trial, Jesse received the highest dose of the virus: 3.8x1013 (380 trillion) viral particles. It caused a violent immune response. Jesse suffered fever, blood clots, and widescale inflammation. Brain damage and organ failure ensued. Four days later, he died.

Some shocking revelations followed. The FDA investigation found that two other participants, who received lower doses than Jesse, had already suffered serious reactions to the adenovirus. This should have stopped the trial in its tracks.

Prior to the human trial, animal studies using a first generation vector saw two lab monkeys die from blood clots and liver inflammation. Jesse was never told this. When the family sued the trial organisers, they quickly settled out of court.

No matter how promising the technology, if gene therapy trials are poorly designed and executed, the results can be devastating.

Even with a good design, testing new drugs is inherently dangerous—that's why trials are necessary. Informed consent and proper regulation are critical parts of the process.

Although the tragedy led to tighter clinical trial regulations, Jesse was not the last to suffer from the experimental platform. Three years later, gene therapy hit the headlines again for the worst possible reasons.

The SCID Kids

Later trials would reveal the long term effects of gene therapy gone wrong.

"Most gene therapies are designed to achieve permanent or long-lasting effects in the human body, and this inherently increases the risk of delayed adverse events." - Gene Therapy Needs a Long Term Approach, Nature

In 2002, a gene therapy trial in France sought to treat babies suffering from X-SCID, another form of Ashanti's severe immunodeficiency disorder. They also received a retrovirus vector targeting complete chromosomal integration.

Initially, the infants responded well and the life-saving trial was deemed a success. But in the years that followed, 4 of the 9 children developed leukaemia, a cancer leading to the excessive production of abnormal white blood cells.

It was a baffling result. The FDA halted all gene therapy trials in the US until the cause could be identified.

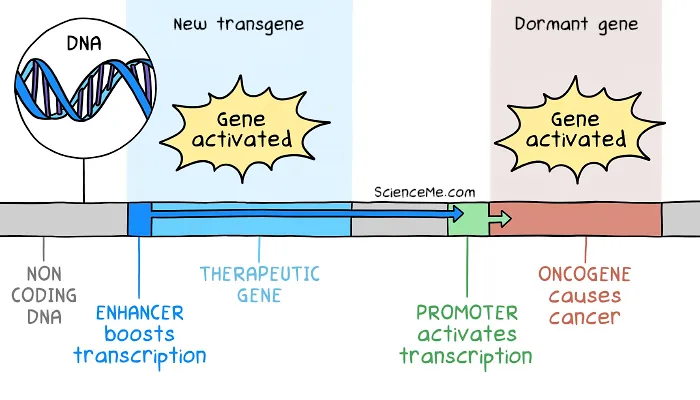

Researchers realised the retrovirus vector had selectively inserted the new genes alongside cancer-causing genes.

Such genes start out as healthy DNA code used in cellular growth and repair. But if they mutate or express at high levels, they become cancerous oncogenes.

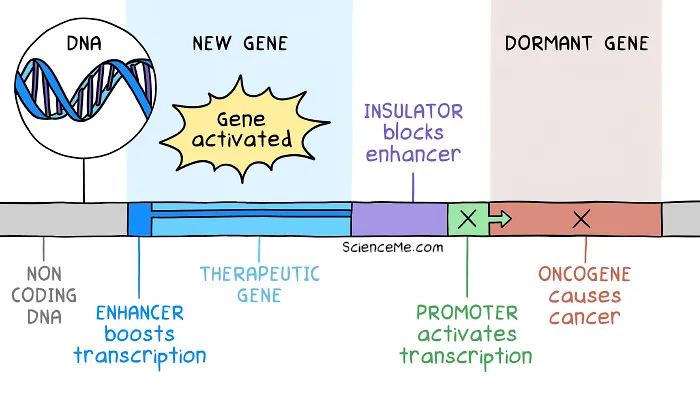

In the SCID trial, the therapeutic DNA included an enhancer region to boost expression. But the enhancer effect drifted thousands of bases downstream to activate dormant oncogenes as well.

How gene therapy caused insertional mutagenesis in the SCID kids.

It's pretty damning when your experimental therapy starts giving children cancer. The episode was widely publicised in the media, and leukaemia eventually claimed the life of one of the children.

An independent investigation concluded that all integrating gene delivery models present the risk of such insertional mutagenesis.

It was a major blow to the field. The trial team raced to find a solution—not least because children were still dying of X-SCID, but the lead researcher himself was dying of cancer.

Their answer was to add an insulator to the therapeutic DNA. Genetic insulators serve as a barrier to limit the downstream effect of enhancers.

Genetic insulators prevent enhancer regions from activating downstream DNA and causing insertional mutagenesis.

Clinical trials resumed with the addition of this safety feature, and the evolution of gene therapy continued.

When Gene Therapy Saves Lives

Gene therapy saw major successes in the years that followed, saving the lives of numerous children born with rare inherited disorders. Here's one such example.

When Amy and Brad Price decided to have children, they had no idea they were both carriers of a single defective gene called ARSA. Their offspring would have a 1 in 4 chance of developing metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD), a degenerative disease that destroys the brain's white matter, leading to paralysis, dementia, and death.

The first time they heard about MLD, Brad and Amy already had two children. One day, their three-year-old daughter, Liviana, complained that her legs didn't work.

Doctors soon diagnosed Liviana with MLD. But since she was already symptomatic, she was past the window for treatment. Testing of her baby brother, Giovanni, showed he had also inherited the disease.

This is common with MLD; families are only alerted to the faulty gene when an older sibling begins to show symptoms. While Liviana passed away from MLD, it provided a vital warning sign so her younger brother could be treated before the disease took hold.

In 2011, Italian doctors drew stem cells from Giovanni and transfected them ex vivo with a retrovirus vector carrying new ARSA genes. Five days later, the modified cells were returned to his body and started producing the missing enzyme.

Now a teenager, Giovanni has well surpassed the life expectancy for infantile MLD, and by all appearances is cured. Brad and Amy Price went on to have six more children, and when another daughter, Cecilia, was diagnosed with MLD, she also benefited from the life-saving gene therapy.

Cases like this provide hope to families in the face of rare childhood diseases. In recent years, gene therapy trials have successfully treated SCID, haemophilia, leukaemia, and blindness caused by retinitis pigmentosa (RP).

Is Gene Therapy Safe?

Successful gene therapy is heavily dependent on choosing the right viral vector, and delivering it at a safe but effective dose.

Take the widely-used adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors. They were once celebrated for their ability to cross the blood-brain barrier, circumventing the need to drill into the skull to treat neurological disorders. But recent animal and human studies have thrown trusted AAV vectors into dispute.

In 2018, an AAV9 vector caused severe toxicity in primates and pigs, leading to liver and motor neuron damage.

The FDA halted human trials using high doses of AAV9 for muscular dystrophy (MD), and investigations into AAV toxicity are ongoing.

It's suspected that high-dose AAV gene therapy may cause DNA damage, stress to the endoplasmic reticulum (a cell organelle used in protein synthesis), and overexpression of transgenes in liver cells leading to liver failure.

To date, 149 gene therapies using AAV vectors have produced serious adverse events at a rate of 35%, with some resulting in death.

Another vector threat emerged in 2021. For the first time in gene therapy history, use of a lentivirus (a type of retrovirus) led to three children developing early-stage leukaemia.

Some suggest the lentivirus isn't to blame, but rather the unique addition of a promoter region triggering genes downstream. Lentiviruses have been used to treat more than 300 gene therapy patients for a dozen different conditions. If research can untangle the mechanism, lentiviruses may still be in the clear.

Discouraged by the risks of viral vectors, some researchers have turned to synthetic vectors like polymers, liposomes, and ultrasound-mediated microbubbles.

While these nanoscale carriers are currently less effective at delivering genes into cells, they are safer and cheaper, while presenting no DNA size limit.

But there's still a question of dosage. Consider the genetic mRNA vaccines that use small doses of lipid nanoparticles to deliver viral genes. This generates low level inflammation, which is ideal for kick-starting the immune system.

But gene therapy is about producing lasting genetic changes. This necessitates much higher doses of both vectors and genes. Scaling the delivery of synthetic vectors could also lead to life-threatening inflammation as seen in viruses.

The safety of gene therapy really depends on the genetic template, vector type, and dosage. Tweaking any variable in the wrong direction can lead to an excessive immune response, gene overexpression, or insertional mutagenesis.

The US now performs two-thirds of gene therapy trials in the world, and by 2025, the FDA is expected to approve 10-20 new gene therapies per year. Beyond rare childhood diseases, therapies are now targeted at common cancer, cardiovascular, infectious, and inflammatory diseases.

This changes the risk-benefit ratio considerably. Children with months to live may understandably be offered last-ditch experimental treatments. Yet the same may not apply to adults with chronic conditions and for which other treatments exist.

Gene therapy is a breakthrough proposition. But not all therapies pose equal risks. Until those risks are understood, each new trial poses a certain gamble in the search for a cure.