Language not only allows us to scheme, coordinate, and express ourselves, it also enables us to think in abstract terms: we can label our objects and concepts, and focus our attention on them. It's all rather wonderful really. But where did language come from?

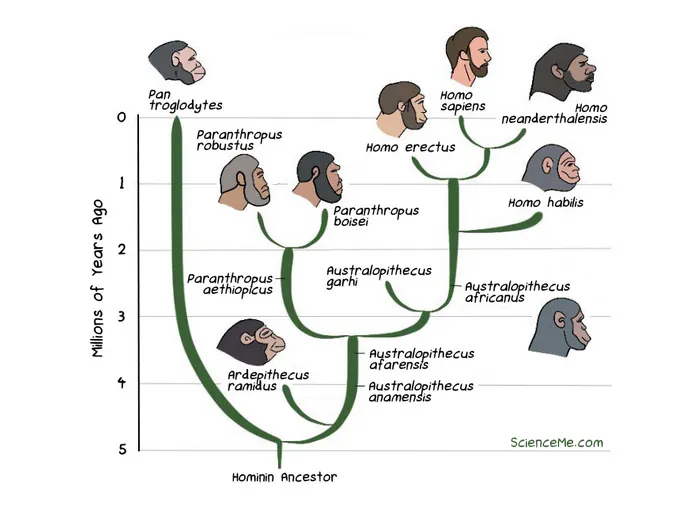

Depending on your definition of human, there have been between three and twenty-one species of humans to walk the Earth.

As Homo sapiens we're the only surviving species of hominins.

Modern humans—Homo sapiens—emerged as a species around 300,000 years ago. Fossil and archaeological records show coordinated groups of human hunters could bring down large prey animals with spears.

Such a feat required not just advanced tool-making, but complex social skills too. Hunter-gatherers were able to forward-plan, strategise, and coordinate through language.

Cavemen didn't convert their words into written language, nor did they annotate their cave paintings for us to analyse today. But there are specific lines of indirect evidence that lead us to this conclusion about the origins of language.

For instance, when the first humans stepped onto Australia 45,000 years ago, the native megafauna were doomed—and not just because of the changing climate. Over a few thousand years, Homo sapiens hunted the Australian megafauna to extinction.

These were beasts they had never encountered before: massive marsupial lions, dragon-like lizards, five-metre snakes, and two-tonne wombats. Nonetheless, humans reigned supreme.

Language is the best explanation we have for this new adaptation, allowing hunters to coordinate their attacks in real time.

Similarly, when humans crossed a land bridge from Siberia to Alaska 16,000 years ago, they thrived by hunting much larger prey animals in groups. The North American mammoths, mastodons, and sabre-toothed cats were soon hunted to extinction.

These prehistoric humans possessed a special form of intelligence, unlike that of any other species. Was it the emergence of complex language? It seems the likely explanation. But what's the earliest direct evidence for the evolution of language?

The Origins of Written Language

At least 12,000 years ago, after all other species of humans had disappeared, Homo sapiens began to shift from a lifestyle of nomadic hunter-gathering to permanently settled farming.

It was soon after the Ice Age when plant domestication arose independently in four locations across Asia and South America. The oldest permanent human settlement is found in the ruins of Gobekli Tepe in Turkey, dated to around 9500 BCE.

Here we find the oldest evidence of a written proto-language. Excavations have uncovered animal-themed iconography carved into stone pillars, including serpents, foxes, boars, and vultures.

But the carvings at Gobekli Tepe are merely pictographs; graphic symbols that convey meaning through their resemblance to physical objects. How did written language emerge and evolve?

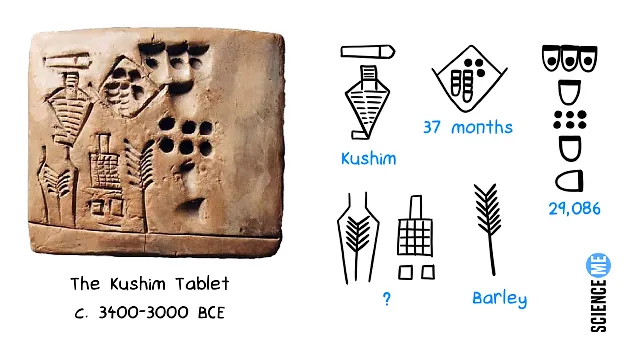

To see the emergence of true written language, we need to go to Mesopotamia, now present-day Iraq. There, from around 3400 BCE, we find the ancient civilisation of Sumeria.

The first written language was developed by the Sumerians of Ancient Mesopotamia.

Tied to the land for plant cultivation and cattle grazing, Sumerian society had a burgeoning economy. Individuals had specific job roles that saw them specialise in a single craft. Trading became a necessity so each family could eat more than a single crop.

In his spellbinding book, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, Yuval Noah Harari explains three factors that explain the origins of written language.

- Memory is limited. Societies developed rules for ownership, trading, and taxation, necessitating the need for written records to keep account.

- Knowledge dies with us. Details of land ownership also had to be recorded so property could be retained from generation to generation without dispute.

- Data gets deep. As new farming technologies and processes emerged, written language was a way to record and share botanical, zoological, and topographical information.

The Sumerians also invented the modern concept of time using base-six numbering, which is why our days are divided in two 12-hour periods, hours into 60 minutes, and minutes into 60 seconds.

Like Gobekli Tepe, early records of Sumerian language take the form of pictographic proto-writing. This system, called cuneiform, was pressed into clay tablets and baked to create a permanent seal.

Cuneiform contained up to 1,500 symbolic icons designed to convey essential information about animals, land, crops, dates, and people.

The Kushim Tablet. The oldest evidence of written language is thought to be an ancient transaction receipt: 29,086 measures of barley were received over 37 months, signed Kushim.

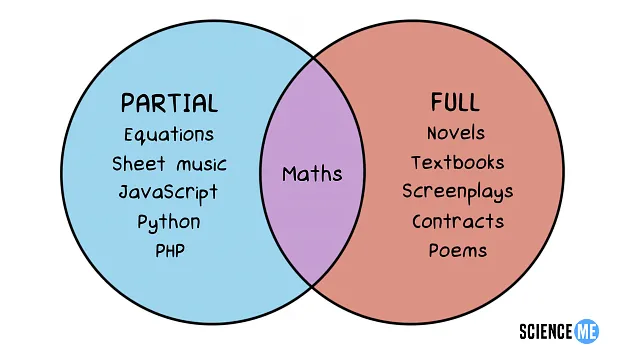

This technical language was a partial script that evolved out of necessity—not to mimic spoken language, but to compensate where human memory failed.

Indeed, we still use partial scripts today in such forms as musical notation and computer programming.

Sheet music is a classic illustration of partial script.

Yet partial scripts are so functionally specific that they can't evolve beyond their technical means. What's more, they're not an intuitive way of thinking. You have to learn the technical rules of each script individually and then adapt your way of thinking to it.

Partial script is a highly technical and condensed written language, while full script is broad, fluid, and compatible with spoken language.

Based on their early pictographs, the Sumerians were the first to develop a more versatile full script that incorporated syllables and structure. By 2800 BC, pictographs were adapted for their phonetic value, allowing people to record more abstract ideas.

As cuneiform script evolved, the pictographic inventory was streamlined to around 600 signs. Many symbols lost their literal meaning and took on phonetic meaning to mimic spoken language. Finally, Sumerians were able to record their epic narratives of kings and battles and floods.

Cuneiform is thought to have inspired the invention of Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics soon after. Such an explosion of written language enabled humans to convey original ideas across space and time. Indeed, Cuneiform was so powerful that it remained in use for thousands of years, right up to the 1st century AD.

The Origin of Maths

Interestingly, maths has qualities of both partial and full script. While encoded by strict technical rules, certain mathematical concepts like quantities or probabilities can also be embedded in spoken language. So where did maths come from?

Maths as a discipline arose in China as early as 1200 BCE, and again independently in Ancient Greece in 600 BCE. The exchange of mathematical ideas between Eastern and Western cultures didn't occur until much later.

The Pythagoreans expanded on basic maths principles using deductive reasoning, rigorous logic, and proofs.

This work was leveraged extensively by the Ancient Romans, who applied maths to engineering, surveying, bookkeeping, solar calendars, and even art.

The mathematical glyphs we use today actually come from India. In 820 AD, Al-Khwarizmi (aka Algoritmi) popularised Indian numerals in his page-turner on linear and quadratic equations. When the invading Arabs saw the value of the system, they spread it throughout the Middle East and Europe on their travels.

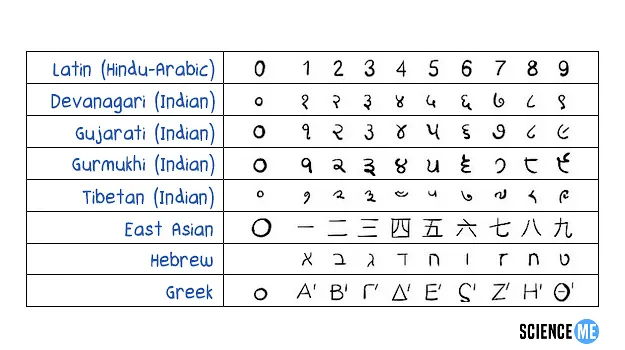

By the 14th century, Hindu-Arabic numerals had replaced Roman numerals. You can see the similarities between Indian glyphs and our familiar numbers of today.

A comparison of mathematical glyphs in different languages.

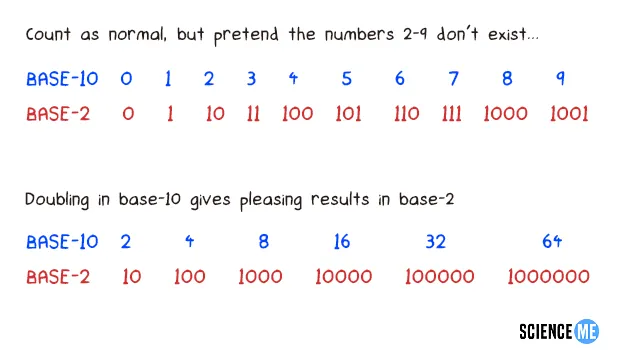

The binary number system used in computers actually comes from the 17th century. It uses a base-2 system consisting of just two digits (0 and 1).

One advantage of binary is that a single digit can represent true (1) or false (0) logic. When you string them together, they can still represent any integer from our familiar base-10 system. It's just a different set of rules. But how in the name of our robot overlords does binary work?

Artificial intelligence uses binary—at least, for now. Even experts find it tough to predict the capabilities of future AI, let alone what exotic languages they will develop on their own. It's plausible, if not inevitable, that artificial general intelligence, or AGI, won't even bother to communicate with humans after a while.

Final Thoughts

Human language evolves continually. Each year, the Oxford English Dictionary adds new official entries like "follically challenged" and "adulting". These are examples of how linguistic evolution is driven by the needs of its speakers. Similarly, COVID meant nothing before 2019, and now we can't go a single day without hearing about it.

This expansion of our vocabulary parallels the origins of language in our hunter-gatherer ancestors. New words emerged slowly: a case of supply rising to meet demand. It wasn't just one chap who sat down and devised an entire dictionary from nothing, as my Nan once adorably proclaimed.

Instead, language is a social construction, born of the need to coordinate, remember, inform, and express. It's entirely fluid and cultured, and humanity absolutely depends on it.