Where Do Cells Come From?

If all cells come from other cells—where did the first cells come from? Take a dip in the primordial soup to see how life began on Earth 3.8 billion years ago according to the RNA World hypothesis.

Once upon a time, there was a primordial soup. It was a tad watery and flavourless, but it did contain some rather promising ingredients for life.

The first cells came from the primordial soup.

Then lightning struck. Or maybe it was a meteorite, or a lava flow, or a hydrothermal vent. We can't be sure until we invent those time-dilating portals to the past you keep talking about.

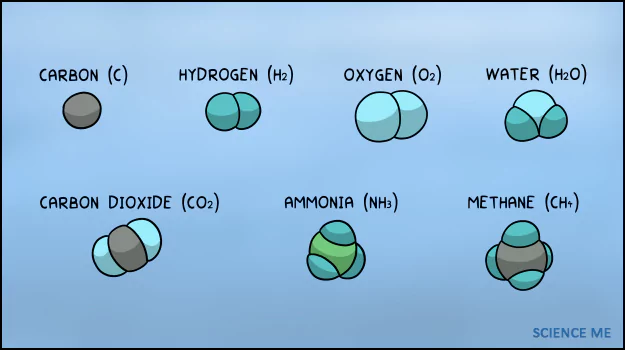

Regardless, the heat source triggered chemical reactions between carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and phosphorus to produce the first nucleic acids.

The First Nucleic Acids

Bingo! Exciting, new-fangled molecules out of a lifeless soup. And it was all down to the innate proclivity for atoms to join into molecules.

Atoms are not goal-oriented. They simply bond with their neighbours according to the laws of chemistry and physics. It's spontaneous, rule-bound, and inevitable.

Nucleic acids were so abundant in the primordial soup that they accumulated, layer upon layer, as brownish crystals on rocks. When ribose sugars (made of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen) joined the party, the first RNA molecule was born.

According to the RNA World hypothesis, the first ribonucleic acid was a chemical inevitability.

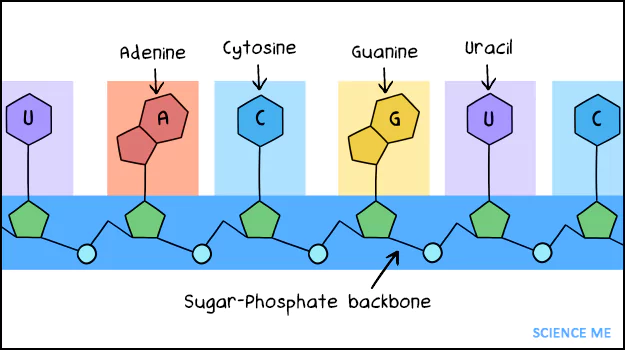

All living organisms have RNA—including humans. It's the single-stranded sister molecule of DNA. And it has some extraordinary properties.

For instance, spontaneous base-pairing means RNA can create negative blueprints of itself. This provided it with the capacity for self-replication without any helper molecules.

What's more, linear RNA strings can loop and fold, prompting internal bonds between the A, U, C, and G bases. This allowed for the development of RNA machines, each functional unit having its own unique sequence, shapes, and length.

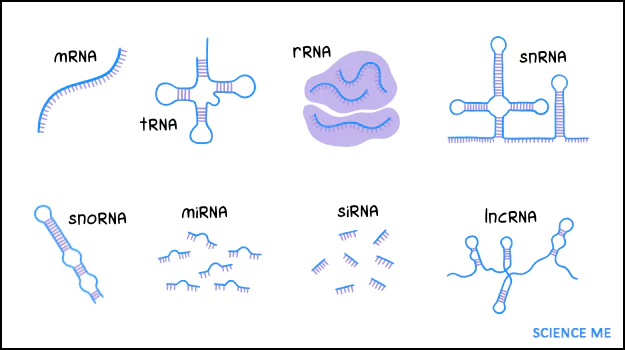

There are many types of RNA in cells, such as messenger (mRNA), transfer (tRNA), ribosomal (rRNA), small nuclear (snRNA), small nucleolar (snoRNA), micro (miRNA), small interfering (siRNA), and long non-coding (lncRNA).

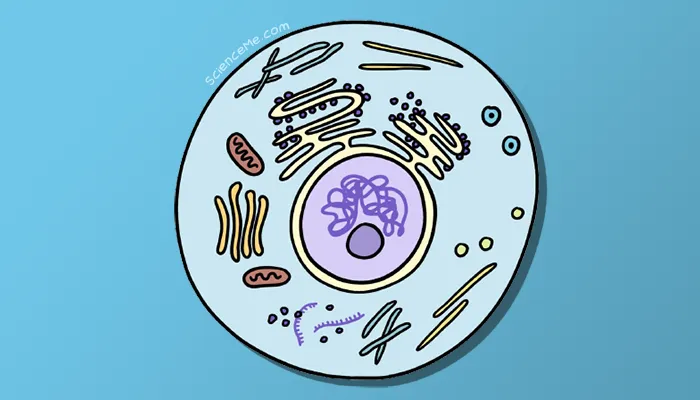

RNA World says that RNA was the first complex molecule in the evolution of cells. Myriad RNA machines performed structural, catalytic, and information storage roles that supported the development of complex organelles.

Where Did The First Cells Come From?

Chemically speaking, RNA was the hard part. The first cells were easy—so long as we're thinking of cells as simple membranes or sacs, separating an interior environment from an exterior one.

How do you create a cell membrane? You need fats—or lipids—which are naturally insoluble in water.

Fats were abundant in the primordial soup. They're simply long chains of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms which, billions of years later, some savvy scientist would name fatty acids.

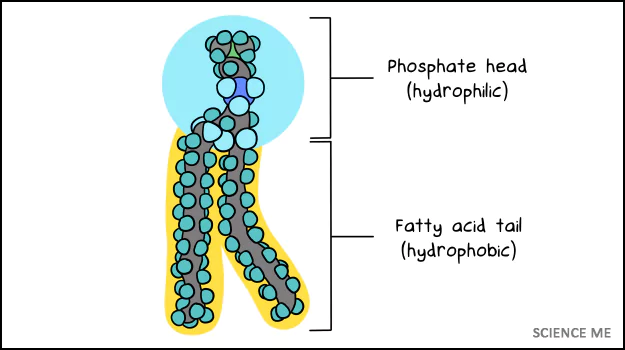

When these linear molecules hooked up with phosphorus and oxygen, they made phospholipids, which have some rather special properties.

Phospholipids self-assemble in water spontaneously to create membranes. This is due to their hydrophilic heads being chemically attracted to water, while their hydrophobic tails are repelled by it.

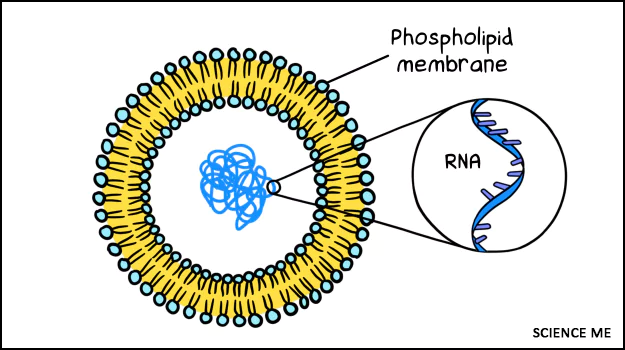

The soup became a bubble bath. And just like bubbles, phospholipids assembled to form bi-layered membranes: tiny spheres with water trapped inside.

With membranes and RNA in abundance in the primordial soup, it wasn't long before the two coalesced. This is ultimately where cells come from.

The first cells came from the primordial soup when RNA became trapped inside lipid membranes.

We're now looking at the most primitive form of Bacteria. With the ability to retain and replicate a basic source code, these were the first living organisms to colonise Earth.

Where Did The First Amino Acids Come From?

Modern cells are much more than RNA and membranes. I'm looking at you, amino acids. These are the building blocks of proteins which do an awful lot of work in cells.

The simplest amino acids formed spontaneously in the chemical soup. But more complex types are only produced through biosynthesis—they're a product of life itself. In this chicken-or-egg scenario, where did the first complex amino acids come from?

Amino acids were routinely deposited on Earth via meteorite impacts. Such events were frequent during the Late Heavy Bombardment around 4 billion years ago.

These extra-terrestrial acid drops still occur today. For instance, in 1969, the Murchison meteorite crashed into rural Australia carrying more than 100 different amino acids. Take that thought to sleep with you tonight as you consider how exactly amino acids came to be on comets in the first place.

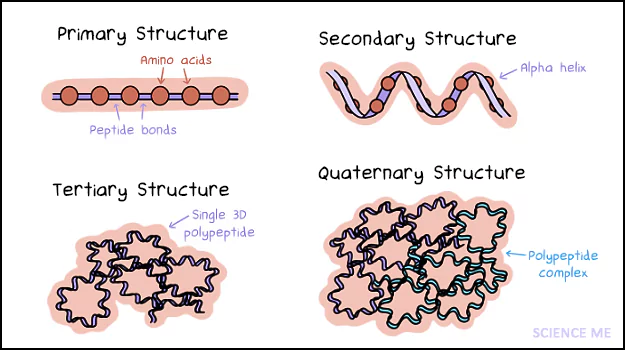

Back on Earth, the RNA machines got to work on the alien molecules. Long chains of amino acids were strung together to make polypeptides, which twist and fold to give rise to proteins. We see these same reactions take place in our own cells today.

How polypeptides fold into complex proteins. Check out the four levels of protein structure: primary (linear polypeptide chains), secondary (helices and pleated sheets), tertiary (3D structures), and quaternary (multiple polypeptides).

As proteins took on new roles in cells—like catalysing reactions and creating internal structure—Bacteria gained better chances of surviving and replicating.

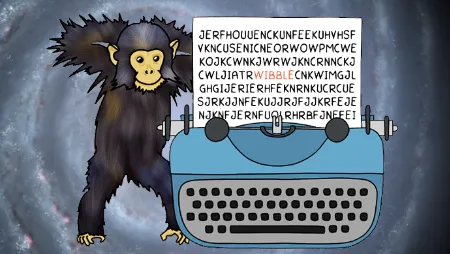

This trial-and-error process meant many early cells were doomed to failure. Cells didn't specify their end goals; nature simply pruned away configurations that didn't work.

Surviving cells propelled their winning RNA blueprints into the next generation. Today, we call these winning blueprints genes. They thrive hand-in-hand with the useful protein products they describe.

With increasing protein and genetic diversity, bacterial cells branched out into many different species. The oldest evidence of cellular life comes from a 3.5 billion-year-old fossil containing no less than 11 different bacteria species.

Now we know where cells come from, or at least, we have one very compelling hypothesis in RNA World. How did single-celled organisms evolve into the complex life we see today?

How Did Bacteria Evolve into Complex Life Forms?

Bacteria evolved on their lonesome for a while. Mistakes in RNA replication led to cellular changes which were either damaging, neutral, or advantageous to survival. This is how evolution works.

Cascades of helpful mutations created novel cell features and behaviours, like the ability for some bacteria to go ahead and eat others. Diversity blossomed.

Eventually, some mutant bacteria took to living in extreme environments like hot springs. They became so diverse they landed themselves a new name altogether: Archaea.

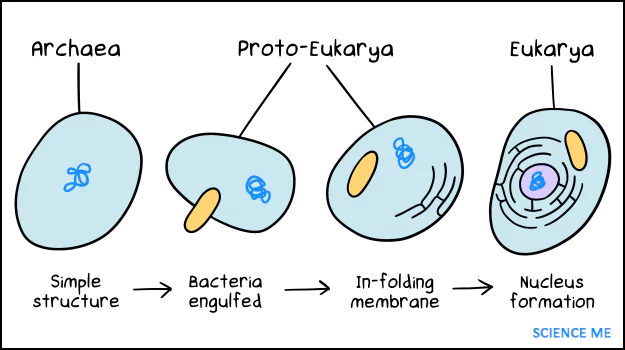

Bacteria and Archaea ruled the Earth for at least a billion years. Then something curious happened. It was a drizzly Tuesday afternoon when a single archaeon engulfed a bacterium. She just clean swallowed him whole.

But she didn't digest him for energy. Instead, she kept him alive and used him as an energy generator. It became a mutually beneficial relationship known as endosymbiosis.

The merging of Archaea and Bacteria produced a new domain of life called Eukarya. Analysis of modern-day algae shows such endosymbiotic events still occur today.

Individually, both cells found this setup rather agreeable. The archaeon gained a second powerhouse of energy, while the bacterium gained an extra layer of protection.

Together they were unstoppable, forming an entirely new domain of life known as Eukarya. Today, eukaryotic cells make up all the plants, fungi, and animals you've ever heard of.

Indeed, almost all your body cells contain symbiotic bacteria called mitochondria. These energy-producing cells live inside your cells, complete with their own mitochondrial DNA.

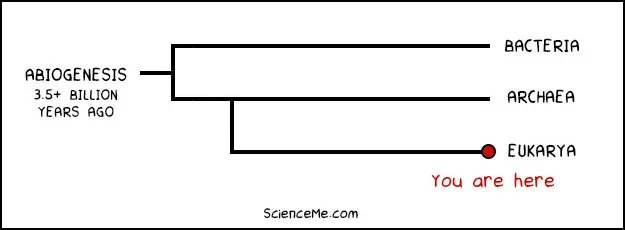

A phylogenetic tree of the three domains of life on Earth.

But wait a second. The first eukaryotes were single-celled organisms, so how did they scale up to become multi-cellular organisms like me and you?

Find out in my bumper post 16 Giant Leaps in Animal Evolution, which tracks the most pivotal mutations in our evolution over the last 800 million years.

How Does Evolution Work?

Evolution connects all life on Earth; whether you're a marine worm or a marmoset, the same genetic code proliferates your DNA.

The Origins of Language

Of all 21 species of humans that have walked the Earth, we're the only ones to develop complex spoken and written language.

Viruses: Genes Gone Rogue

Viruses are essentially runaway genes, also known as intracellular parasites, mobile genetic elements, or freeloading gits.

How Does ChatGPT Work?

ChatGPT is a Large Language Model that uses machine learning to do some very clever things that will not literally blow your socks off.

The Evolution of SARS-CoV-2

The family tree of human coronaviruses and how SARS-CoV-2 mutates through the process of rapid antigenic drift.

The Life of Isaac Asimov

Asimov was intent on raising the intellectual awareness of America, fearing that otherwise humanity would become its own downfall.

Who Owns Your Organs?

It's not you—it's me. While the Veto Rule is standard practice in many nations, it raises a little-known ethical dilemma.

The Life of Elon Musk

So you have this dream of changing the world? For Elon Musk, this isn't enough. His ambitions are multiplanetary.