It's not you—it's me. Besides a pseudo-compassionate breakup line, it's also the answer to this ethical minefield of a question.

If you pass away tomorrow, it's actually not your decision if your corneas, heart, lungs, kidneys, liver, pancreas, and skin are harvested and given to transplant patients. Whatever it says on your driver's licence, it's actually your family's choice whether to donate your body.

This "Family Veto" rule is standard practice in many developed nations—but it raises a little-known ethical dilemma that could cost lives.

Here in New Zealand, when the opportunity for organ donation arises, half of all families say no. Yet frequently, their dying loved ones were willing donors.

Indeed, New Zealand and the UK have among the worst donor rates in the developed world, with only 12 deceased donations per million people. The US does better with 26 per million. But first place goes to Spain, whose people donate organs at a rate of 40 per million.

Now, 40 donors per million people still sounds pretty low, but we'll dive into what that is in a moment. First let's take a look at the ethics of the contentious Family Veto.

The Ethics of Organ Donation

The philosophy of utilitarianism says that when we're confronted with an ethical dilemma, we should weigh it up in terms of overall utility. In other words, seek the greatest balance of benefits over harms for everyone involved.

Utilitarianism would have us abolish the family veto straight up. It results in a fair distribution of resources in a life-or-death scenario.

But some ethicists decry this response. Families may feel that harvesting their loved one's organs is itself inhumane. The black-and-white argument of Utilitarianism is merely an objective solution to the problem. It lacks subjectivity and compassion; a fact that chips away at its moral high ground.

However, the Family Veto raises its own dilemma. When you're on life support, your rights are legally transferred to your family so they can make the most up-to-date decision on your behalf.

But can we trust their judgment? Handing your rights to your spouse or relative tramples on the increasingly popular mantra of "my body, my choice".

Other end-of-life legislature doesn't succumb to this loophole. Legal wills and do-not-resuscitate orders are put place when we're alive—and they hold firm when we die. There's no precedent for our grieving family to overrule our wishes. So why is organ donation different?

The main tangle comes down to informed consent. Wills and DNRs are legally binding documents, created with care and consideration, witnessed by lawyers or doctors. This isn't true for organ donor registration.

In many countries, your donor status is a yes-or-no checkbox on your driver's licence application, which doesn't actually constitute informed consent.

Instead of trampling your rights, the Family Veto was actually set up as a protection. It enables your next-of-kin to make a fully informed decision based on the circumstances. So what new information could they have at your deathbed that you lacked when you made the decision? And does it matter enough to risk overruling your wishes?

Utilitarianism in Action

Here's what happens in countries where the state owns your organs, and the family has no influence at all. It's a deeply uncomfortable look at how donor laws can backfire.

In Singapore, the Family Veto was abolished in 1987, along with a new dictate that all citizens are automatically organ donors unless they actively opt-out of the system.

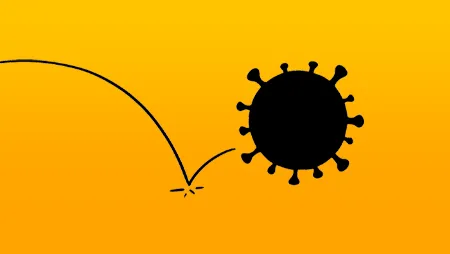

When 43-year-old Sim Tee Hua suffered a stroke, he lay on life support surrounded by his family. Doctors concluded there was no chance of recovery, but his family wanted more time. They were hoping for a miracle, but that hope was all they had.

Hua hadn't opted out from organ donation, and his condition made him an ideal donor candidate. His doctors were legally obligated to follow the utilitarian solution, and harvest his organs before time ran out.

There's a small window for organ retrieval: while the patient is still alive, usually on life support, before the organs lose blood supply and shut down. This makes organ retrieval surgery the technical cause of death.

Few people can comfortably seal the fate of a loved one for the benefit of a stranger. In these scenarios, the value of the Family Veto becomes clearer. Except in Singapore, there was no veto. The ensuing scene was a dystopian nightmare.

Police and hospital security restrained the family by law, while medical staff took Hua into surgery to retrieve his organs, thereby instrumentalising his death.

The family were left with two traumas to process, giving us a disturbing glimpse of what can go wrong in a system that's ultimately geared to value human life. Moreover, the media coverage of Sim Tee Hua was extensive, leading to a public outcry and a significant drop in national donor rates.

Today, Singapore's donor rate is just 8 donations per million. What was designed as a fair distribution system became a lose-lose situation in practicality. Transplant patients still die on waiting lists while grieving families still suffer seeing their loved ones taken away against their will.

Singapore's auto opt-in system raises more ethical quandaries. If you opt-out of being a donor, does that mean you shouldn't be eligible to receive a transplant yourself? What if you opt-out on religious grounds? Should children and mentally disabled people be automatic donors? Should caregivers be allowed to opt-out on their behalf?

Just because we have a medical technology at our disposal, does that mean everyone should be on board with it? Governments have to tread a fine line when it comes to respecting individual beliefs, lest they fall into authoritarianism. Opting-out of a life-saving system might make you selfish or it might not. But the choice to do so is what matters; it's a marker of a healthy, free society.

Finding The Balance

Still, organ donation is the last thing people want to think about when it matters most. So how can medical staff broach the topic better at the critical moment?

With the highest rates of organ donation in the world, Spain set the global standard in the 1990s. Like Singapore, Spain runs a system of presumed consent, with the choice to opt-out. But unlike Singapore, it also has a Family Veto law.

How does this pan out in reality? Presumed consent raises donor transplant rates by 25-30% both directly and indirectly. There's more public awareness of the need for organ donors, while assuring people that their sacrifice is also their gain.

At the same time, the boost in organ donors affords hospitals the opportunity to honour the Family Veto in certain circumstances. And in turn this eliminates the risk of forced-harvesting events that spook everyone.

The Spanish government also has dedicated Transplant Coordinators at the front line. Donor candidates most often come from the ICU, so this is where they train up specialists to have intimate involvement in the decision-making process.

Transplant Coordinators excel at respectfully nudging families toward donation at a time of great stress, confusion, and uncertainty.

For comparison, less than half of New Zealand health professionals said they raised the topic of organ donation with candidate families last year. The same problem occurs in the UK: while 80% of health professionals are pro-donation, many fear putting further stress on families in their darkest hour.

How to Increase Organ Donor Rates

Studying these different approaches gives governments the opportunity to see what works—and what doesn't. Many developed countries can still take steps to raise national donor rates. The question is will they make the investment?

1. Create an Official Donor Register

Logging donor status driver licences leaves millions of non-drivers out of the equation. This is low hanging fruit. It also tackles the problem of informed consent. An official register can lay out all the emotional and practical outcomes of organ donation, and let people decide for themselves before making a firm commitment. This, too, reassures our families about our intent, making them less likely to veto organ donation at the critical moment.

2. Invest in Public Awareness Campaigns

There's a clear financial case for governments to invest in promoting organ donation. Patients on transplant waiting lists incur significant healthcare costs, as well as increasing patient load. Take kidney failure for example: the financial burden of ongoing dialysis and living subsidies far exceed the cost of transplant surgery.

3. Train Transplant Coordinators

Medical staff can have a hard time approaching grieving families. Yet when they miss the critical window, they not only deny transplant patients their chance for a normal life, they also deny families the potentially healing act of altruism. With additional training, more healthcare workers will be able to raise donor rates at the organisational level.

Final Thoughts

Organ donation is an ethical and logistical minefield, with plenty more personal, political, religious, and philosophical perspectives to consider. It's a deeply personal choice, worth talking about with your loved ones today. Because your worst case scenario could be the key to someone else's life—and vice versa.